The Usual Game Scenes

Last time, I forgot to mention The World Ends With You (TWEWY); I love it and it’s an example of a very different JRPG. Anyway. A fine article about JRPGs can be found here. In particular, the ‘Managing Game State’ section was quite illuminating and I’ll talk a bit about it here. Games can be seen as a set of states: I think of them as a set of graphical elements and allowed interactions, plus rules for changing the active state. I’ll use the term scene for game states, as it’s the way I think they would be implemented in Godot.

There are scenes that are commonplace in JRPGs: a local scene, a world scene, a combat scene and a menu scene.

The Local Scene

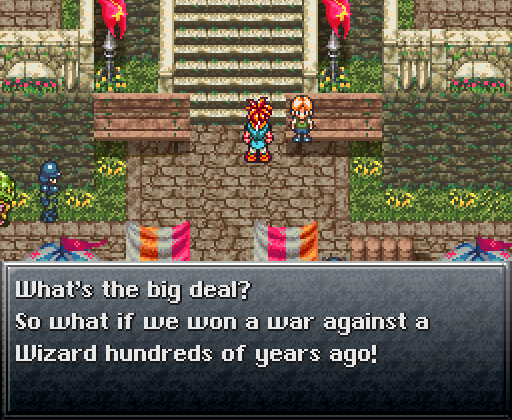

This is where most of the plot-related activities happen. For example, the player can explore cities, talk to non-playable characters (NPCs), buy and sell stuff, solve puzzles, accept sidequests, etc. This is where the player usually has the most freedom of movement; there is a good amount of graphical detail, as the player is expected to spend a good amount of time in this mode.

I’m not sure if it’s possible to have a JRPG without a local scene. I think turn-based strategy games like Final Fantasy Tactics tend to replace free exploration with lengthy battles where worldbuilding and story-related events can happen.

Some examples

-

The first few generations of Pokémon games and Final Fantasy VI have Local Scenes where player movement is restricted to a grid. Talking with NPC locks the player in-place.

-

Chrono Trigger, Radiant Historia, TWEWY and others have free, unrestricted movement. In particular, Chrono Trigger allows for moving away from NPCs while talking to them, which cancels the conversation after a certain distance.

The World Scene

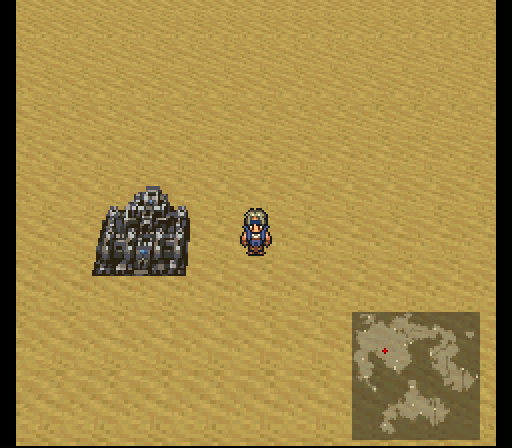

This scene is a “zoomed-out” version of the Local Scene. Also called “the overworld” in some contexts. One of the reasons for this scene’s existence is that, as the local scene is meant for players to explore town-sized locations, a story that involves a full world at this scale would be unfeasible. Therefore, it’s common that exiting a town lands the player in the World Scene.

In the World Scene, the players can move between relevant locations. Reaching a location lets the player see their name and enter its Local Scene version. World Scenes can vary in their degree of freedom: the more restrictive ones are basically glorified menus overlaid on a map, while others allow for some of the Local Scene interactions. Many games where the player can freely move in the World Scene allow for random enemy encounters in it.

One of the benefits of having a World Scene is being able to give the game a sense of scale; for example, the game can show the World Scene being affected during a cataclysmic event. However, having a World Scene usually requires creating additional art.

Some games do not have a World Scene. The Pokémon series, for example, only has a “Map” item that lets the players check the towns’ relative positions, but all travel is done in a Local Scene, full of NPCs and puzzles. Many modern RPGs, especially 3D ones, also lack a World Scene, as they tend to present the player with a huge, interactive world. This gives the player bigger freedom, as they can interact with every location in the game world; this allows for more sandbox-styled games. Other games don’t have a World Scene simply because the scope of their stories don’t need one.

Games lacking a World Scene usually include a map in the Menu Scene; in addition to this, many of them offer some sort of fast-travel mechanisms in order to allow the player to quickly return to places they’ve already explored. Many games with a World Scene lack a fast-travel option, opting to invoke the Global Airship trope instead.

Some examples

-

Final Fantasy VI and Golden Sun have a World Scene where the player walks between locations, with random enemy encounters.

-

Chrono Trigger has a World Scene like FFVI’s, but without random encounters. It is used in cutscenes, though.

-

Chrono Cross’ World Scene is similar to Chrono Trigger’s, but it’s not used in cutscenes (as they’re full 3D animations).

-

Radiant Historia has a a series of locations and roads overlaid on a map as its World Scene, which only allows for discrete movement. World-scale events are shown using multiple Local Scenes, as the World scene is barely more than a map.

-

Undertale and TWEWY don’t have a World Scene, as their worlds are somewhat small.

-

Pokémon doesn’t have one either; even though its world is bigger than Undertale’s and TWEWY’s. This is compensated by having a fast-travel system.

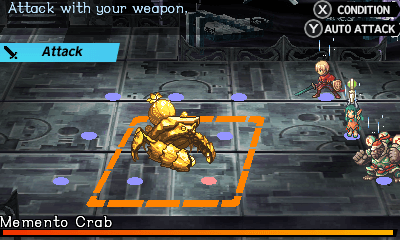

The Battle Scene

Most JRPGs have some sort of combat, ranging from full action RPGs like the top-down Zelda games and TWEWY to the strict turn-based system used in the Pokémon series. The less real-time, action-based combat and the more turn-based, command-based combat has a game, the more likely it is to have a specific scene for its battles.

Battles are usually entered from the World and/or Local Scenes, depending on the game. The Battle Scene can have its own custom background or be overlaid on the World/Local Scenes. If the game has specific mechanics such as a grids (Radiant Historia does this), the game will probably use a completely different background for its Battle Scene.

RPGs without a Battle Scene can be games where the action takes place in the Local Scene (e.g. most 2D Zelda games) or games where there’s no fighting at all.

Some examples

-

Undertale, Chrono Cross, TWEWY, Final Fantasy VI, Golden Sun, Radiant Historia and the Pokémon series have a fully separate Battle Scene. Final Fantasy VI and Golden sun can enter the Battle Scene from both the Local and World Scenes; the others can only do so via the Local Scene

-

Chrono Trigger overlays its battles over the Local Scene, but it’s a distinctly separate scene (as controls and mechanics are completely different). This fits with its fixed, Local Scene-based encounters instead of having random encounters.

-

2D Zelda games have their fighting in the Local Scene: there’s no separate Battle Scene.

The Menu Scene

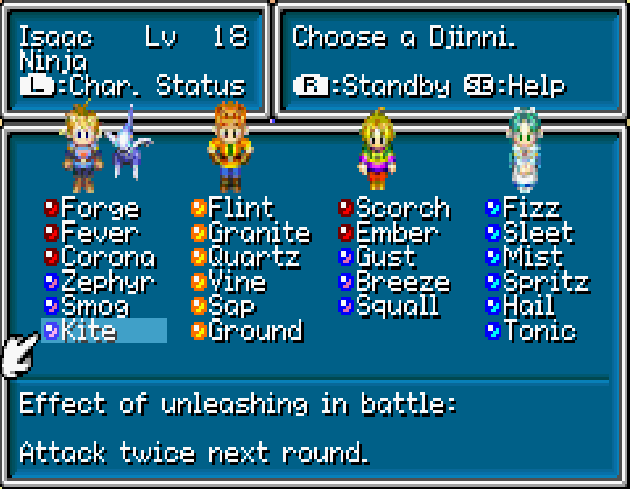

If the World and Local Scenes are where most of the plot takes place, and the Battle Scene is where most of the action takes place, the Menu Scene is where most of the customization takes place. First, this scene can be used for in-universe actions such as using items, assigning equipment to characters, checking characters’ status and selecting and using character techniques for recovery or puzzle solving. A second set of actions are out-of-universe actions, such as saving progress (which can have an in-game metaphor), selecting UI, video and audio settings.

The Menu Scene can usually be accessed from the World and Local Scenes, and might cover the current Scene fully or partially.

Some examples

Most games have Menu Scenes in one way or another, so the following are examples that are interesting in one way or another.

-

Golden Sun and the Pokémon series implement techniques through which the player interacts with world elements, such as pushing stones, freezing water and cutting down bushes in order to reach new areas. Both of these games also allow for abundant team/party customization, making the Menu Scene very important.

-

Final Fantasy VI, Chrono Trigger and others allow using healing techniques outside of battle, through the Menu Scene.

Phew!

So, what am I gonna do? I’m thinking of the following:

-

A Local Scene with free, gridless movement.

-

A simple, Radiant Historia-like World Scene.

-

I’d like to reproduce Chrono Trigger’s Local Scene - Battle Scene transition (i.e. overlaying the characters in the Local Scene as they battle)